Last month’s Habanero left off with a synopsis of the lack of efficacy of COP28 (the 28th “Conference of Parties,” the supreme decision-making body of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) and predecessors, culminating with commentary on a social phenomenon that has become known as Toxic Optimism—an effect whereby “doomers” are (ironically?) shamed into silence because we should all suppress or dismiss concepts that invoke unpleasant emotions, thereby ensuring that we do not engage in authentically reflective conversations about how to collaboratively address major environmental issues of our time.

The discussion on Toxic Optimism, a behavioral phenomenon, is a nice segue into discussing a recent research paper/mini-review characterizing the Global Human Behavioral Crisis (“Merz et al.”), causes and controls of said crisis. Authored by a large international team of scientists, including lead authors from New Zealand and collaborators from prestigious universities and organizations in Australia, Canada, South Africa, the US, and the UK, the paper is catching a lot of buzz in the scientific waters I troll. Perhaps this buzz is due to the degree of interdisciplinarity in content and message, and in large part, one imagines, as the message is so resonant for any scientist with a reasonable range of interdisciplinary environmental understanding.

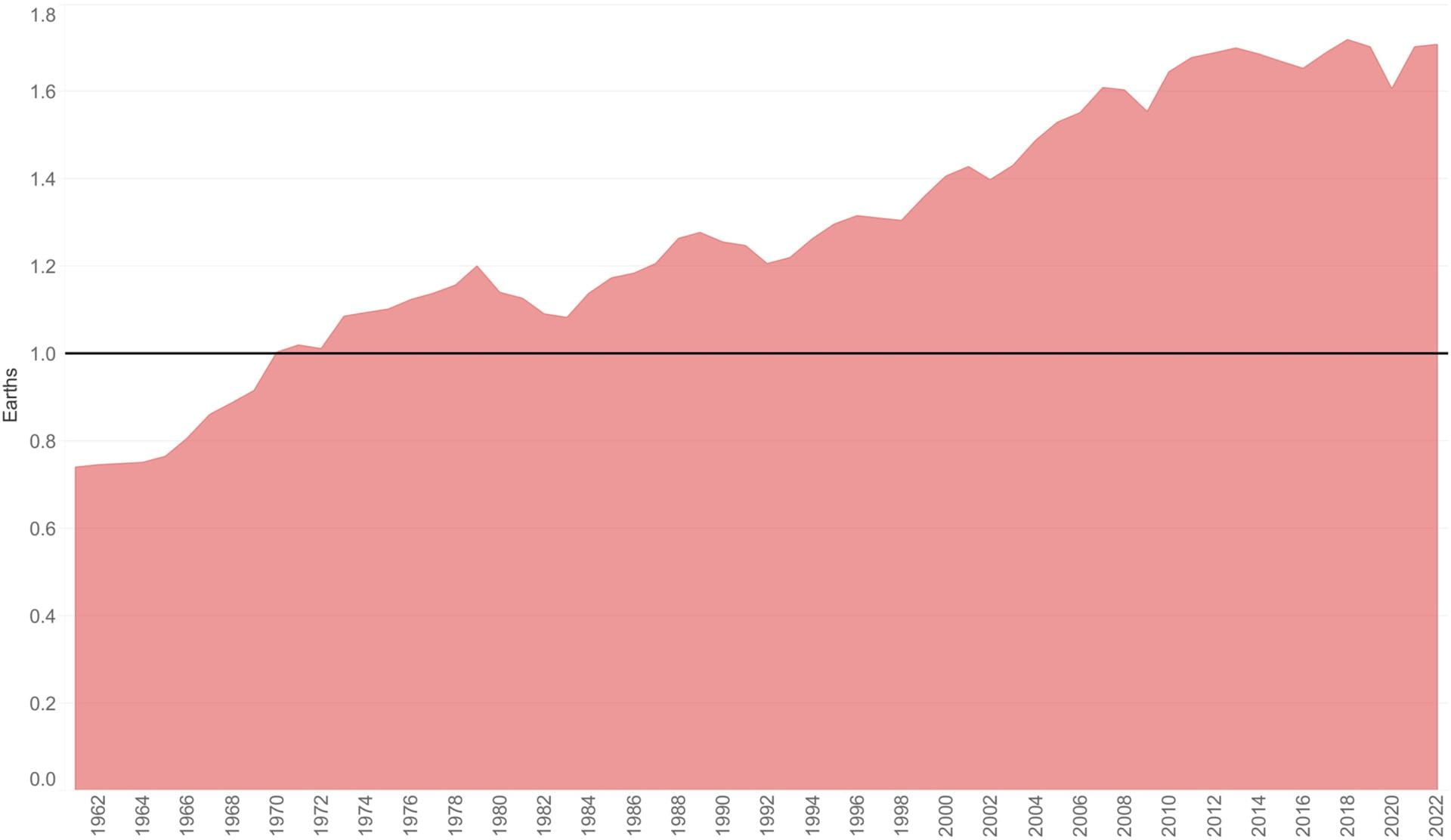

The paper begins by pointing out the fallacy of having a uni-dimensional focus on climate change, noting that massive rates of local, regional, and global biological extinctions, land-use change, pollution, freshwater change, change in natural chemical cycles (particularly by the use of nitrogen and phosphorous fertilizers), along with climate change, all do their part to intensify the rate and magnitude of environmental degradation in a manner that is unsustainable for life as we know it. Unsustainable change is a symptom: overconsumption, waste, and population are the causes. The figure below illustrates the central issue in a nutshell; humanity’s use of Earth’s resources has exceeded replenishment. This is, in effect, like spending money in the bank without putting more in; fine for now, while it lasts.

The graph above from Merz et al., 2023, shows how many “planets” worth of resources humanity is using (vertical axis) by year (horizontal axis). The Earth can no longer pay into our account proportionate to our use, while the spending party that began circa 1970 becomes wilder every year while the account’s “monetary stock” lasts.

Source: Merz JJ, Barnard P, Rees WE, Smith D, Maroni M, Rhodes CJ, Dederer JH, Bajaj N, Joy MK, Wiedmann T, Sutherland R, 2023. World scientists’ warning: The behavioural crisis driving ecological overshoot. Science Progress, 106. doi:10.1177/00368504231201372

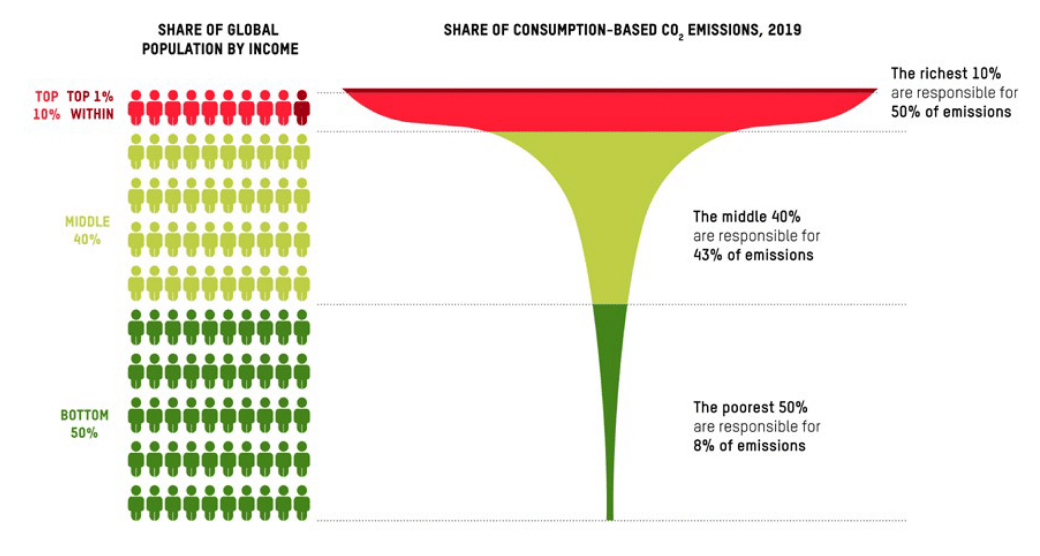

Population growth is an issue in some regions of the world; however, in the developed world, consumption and waste are the main issues. Merz et al. cite data showing how the portion of the population with incomes in the bottom 10% globally contributes just 3–5% of environmental impact, with the bottom 50% contributing only ~10% of CO2 emissions, while the top 20 wealthiest individuals on Earth produce 8,000 times the carbon emissions of the poorest billion people (figure below graphically illustrates wealth versus emissions).

Martini, anyone (to match the shape of the graph)? Those of us living in the US are definitely in the glass completely full category, i.e., the red in this figure. Source: Population Connection

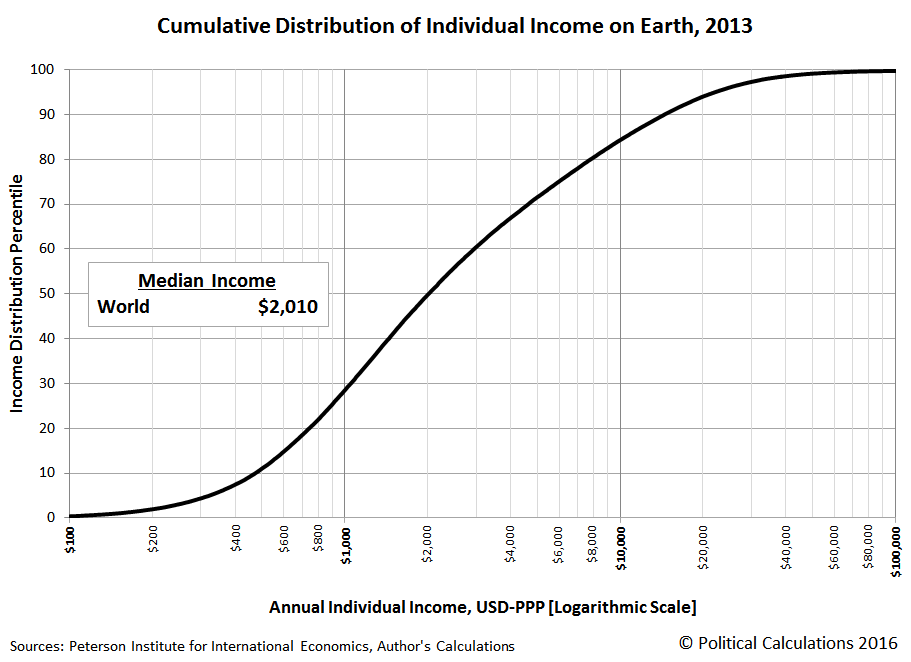

If you are wondering where you fit into this, allow me to be of assistance: if you earn more than US $14,000 per year, on a “parity basis,” i.e., adjusted for spending power to be on a level world playing field, you are in the 10% showing in red in the graph above. If you earn more than US $58,000 per year, you are in the top 1%, shown in dark red at the very top of the martini glass in the graph. Where these numbers fall in wealth calculators vary; however, I have yet to find one that does not put most people living in the US well into the 10% mark; many Americans who consider themselves ordinary are nonetheless in the 1%. The numbers are clear—overconsumption and waste trump sheer population numbers for environmental damage, and one does not need to be flying private to Davos to do their part to contribute to the damage profile.

Global wealth (on a parity-adjusted basis reflecting spending power on a globally leveled playing field) and how much income one needs to be wealthy or poor on a global basis. Values shown on the horizontal axis are adjusted to US dollars. Source: Political Calculations

In a gravity-defying feat of teeth-rattling bravery, Merz et al. go beyond the call of duty for a research paper and dig into the causative factors of why we overconsume for no particularly great reason other than that we can. After all, research shows that in terms of many indicators of life quality (access to medical care, education, happiness), the rich of the world could live off 25% of what we now do without substantive diminution to our indicators of well-being.

Consumption – our daily choices accumulate into a global impact. Source: Peachy Essay

One cause of overconsumption for overconsumption’s sake is that economists have been of the view that economics is decoupled from natural resources, in stark contrast with the biophysical facts. Biophysically, the fact is that the 100-fold real gross world product increase since the early 1800s was only possible by technologies that use fossil fuels and that this 100-fold economic growth was accompanied by a 175-fold increase in fossil fuel use over the same time (Merz et al.; also see other Habanero posts linked herein). While it is comforting to think that renewables will be able to replace fossil fuels, 1) that is not happening, and 2) (in simple terms) renewables do not have the same energy return as fossil fuels to achieve such an outcome (which may relate to #1—why it is not happening).

Economists are famous for their understanding of economics, not biophysics. Source: Made of Money.

Another issue is much deeper and a combination of two factors. First, and fundamentally, we are animals, biologically programmed to seek pleasure, avoid pain, acquire, amass, and defend resources from competitors, display dominance and status, and procrastinate rather than act whenever action does not have an immediate survival benefit, particularly for ourselves or close relatives and territories.

You and me baby ain’t nothin’ but mammals…Source: Giphy

Second, we are animals constantly subjected to behavior manipulation via marketing and, well, Toxic Optimism. Those top 20 wealthiest individuals on Earth who produce 8,000 times the carbon emissions of the poorest billion people will not stay there without our concerted support. And we all need to do our part for our respective positions in the top 1% (or 10%, as the case may be). Merz et al. describe the behavior manipulation transition that I have witnessed over my life. My grandfather, born in the 1800s, bought toothpaste as a matter of maintaining personal hygiene. During my parents’ lives and now my life, toothpaste morphed into a product that the Merz paper accurately describes as a “mint-flavoured confidence boost,” something that could make one feel more attractive. Behavior manipulation of consumers is relatively easy now due to the collection and sale of an individual’s personal data; in the US, Merz et al. point out, we each have our personal online data tracked and shared 747 times per day on average, or 294 billion tracks each day for the USA. More shocking, Ad Tech companies hold an average of 72 million data points on the average US child by the time the child reaches the age of 13.

The lack of sense in the consumptive trajectory of humans in view of outcomes led Merz et al. to discuss matters in terms of a Global Human Behavioral Crisis rather than a global environmental crisis. They have a solution—behaviorally manipulate consumers of the world to signal individual value through nonconsumptive pathways—so, for instance, we might all begin to assign value to ourselves more based on whether we are kind than whether we acquired many New Objects of Desire from Amazon Prime. Aside from the ethical issues around this noncommercial use of behavior manipulation, Merz et al. admit, however, as with many other proposed solutions, time is short, and action is deficit. Still, it’s an interesting read, relatively short, and open access. Check it out.

It seems obvious because it is: “behaviorally manipulate consumers of the world to signal individual value through nonconsumptive pathways,” but nobody’s gonna make money that way…

Completely agree. In theory, the transition to “new economy” would need to happen. In practice, that does not seem to be a very well-disseminated concept, much less popular.