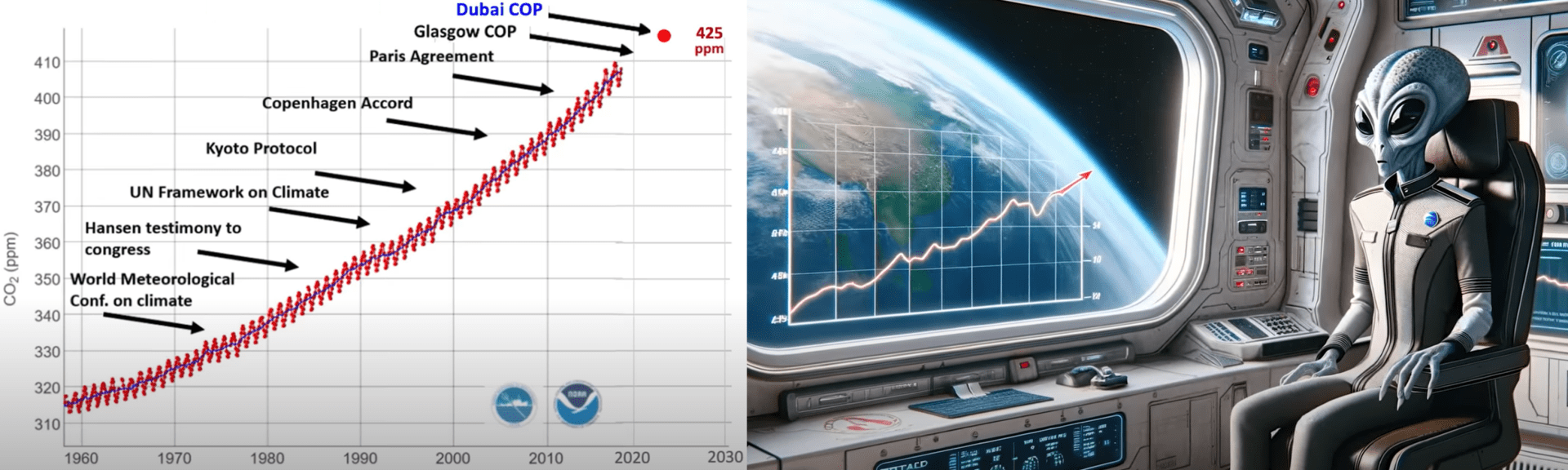

December 12, 2023, marked the close of COP28, i.e., the 28th “Conference of Parties,” the supreme decision-making body of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change whose task could be summarized as bringing world leaders together to agree on a way forward to reduce emissions. There may be a heretofore unexplored relationship between the COP meetings themselves and the rising planetary atmospheric carbon dioxide, CO2.

As Nate Hagens, Executive Director of The Institute for the Study of Energy and Our Future, recently pointed out: if a space alien were to visit our planet and examine climate data (CO2, a chemical measurement) as a function of COP meetings (a social indicator), such a visitor might hypothesize that COP events could themselves be the cause of CO2 increases. In any case, the data categorically do not support a hypothesis that COP has ever, or could ever, produce a productive outcome if emissions reductions are the goal.

One does not require the sophistication of a galactic traveler to see that COPs are not slowing CO2 emissions.

Hagens discussed the ineffectiveness of COP via the lens of what used to be known as cultural hegemony—social dominance over the diverse thinking and mores of the many via social pressure and suppression of views by the few, the powerful. Decades of research later, we now speak quantitatively in terms of the Power Distance Index, which reflects the unequal distribution of power in workplaces, organizations, and societies and the level of acceptance of that inequality.

Research has repeatedly shown that in organizations with high Power Distance (more autocratic or paternalistic), subordinates are hesitant to express opinions freely to superiors, stifling cognitive diversity, creativity, teamwork, and innovation, i.e., the exact qualities needed to address some of the most extreme environmental challenges that the world faces today (for further reading, see links below). In consequence, there are a large number of publications that equate transformational leadership with lowering Power Distance. In his blockbuster book: Outliers: The Story of Success, Malcolm Gladwell devotes a chapter to the topic of low Power Distance and success, one example being how, in the late 1990s, Korean Air had a plane loss rate that caused other major international airlines to cancel partnerships with them. Korean Air recovered by instituting a groundbreaking training program effecting cultural change to lower its Power Distance Index.

I have had a palpable personal encounter with Power Distance Index; while writing this article I discovered that, out of the very many countries in which I have lived, the one where I felt the greatest freedom of inquisitive discourse has the second lowest Power Distance Index globally. My primary country of citizenship, New Zealand, ranks fourth lowest, with a Power Distance Index that is half that of the USA—now I can point to quantitative numbers that accurately reflect my perceptions of the differences in the discourse that is possible between countries.

In recognition of the Power Distance conundrum and how much humans *really* care about their reputation, job, status, and public perception, Hagens proposes using technology to allow COP delegates to ask completely anonymous questions without recourse to their reputation, job, or status. Here are examples of a few delegate questions under Hagens’s approach:

- “Can we all first agree that we have failed in these 36 meetings to limit global carbon emissions, and can we discuss why that is before we go any further?”

- “The world currently uses 19 TW of power continuously. Due to our focus on climate, we are now adding 1 GW of solar photovoltaic capacity per DAY! (Yay!). However, to reach 19 TW at this pace would take 270 years. Even if we could ramp up our current rate by a factor of 10 to 10 GW per day, it would still take 27 years, which is also the expected lifetime of the solar equipment, so we’d have to do this continuously forever for replacement. Said differently, our current 1 GW a day rate of solar photovoltaic expansion manages to get 1.9 TW average power installed in 27 years, so we could support 10% of our current energy demand at the current (breakneck) rate of installation. Even were this possible, it would perpetuate a tailspin in materials and ecological consequences. Not gonna. When can we state this aloud and start realistic plans?”

- “Are we here to solve the climate situation? Or have these meetings evolved to maintain our social power and bootstrap our preferred cultural strategies?”

- “What if every time ‘reducing emissions’ was mentioned in the 4,900-page IPCC Climate Report, we replaced it with ‘reducing energy and material use’ – would that change our impact? Or would it end our funding?”

- “This is my 9th COP. I begin to wonder – how are these conferences different than arguing with a forest fire, but with good food?”

- “Would it be possible for everyone – before they speak at this plenary in the next 10 days, to preface their contribution by sharing one profound personal experience they’ve had in nature?”

- “Is anyone else embarrassed to be here?”

- “J – lets meet at the bar? – if we miss I am in room 355”

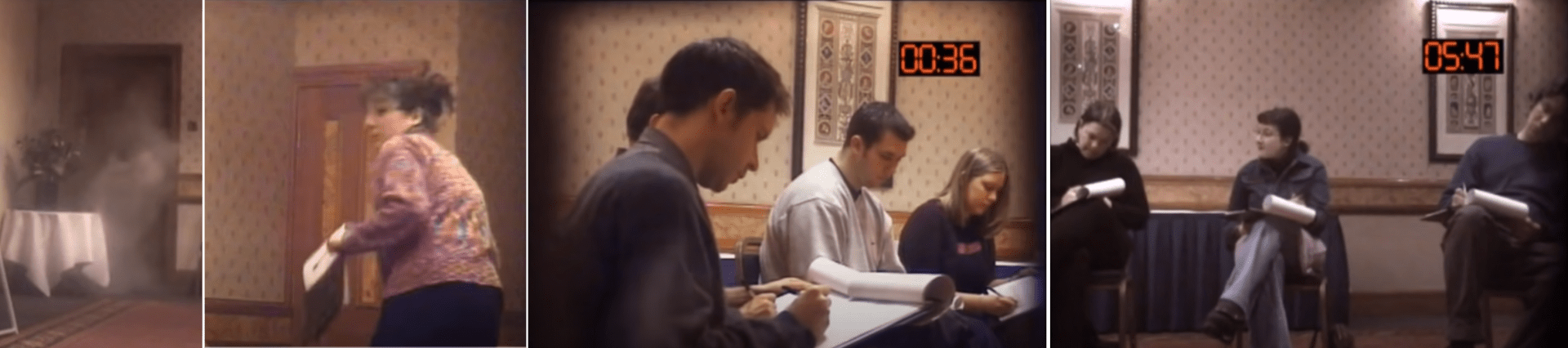

As modest a proposal as Hagens makes, however, the problem goes deeper than the ability to ask questions freely. Ideally, questions lead to a conversation. Hagens points out the difficulty of having a conversation as a result of an effect that some refer to as dangerous conformity. Dangerous conformity is a concept many know through the “Smoke Under the Door” study, wherein 90% of participants failed to react to or report copious amounts of smoke coming under a door in their room accompanied by a fire alarm (simulating fire in the next room) if others present seemed unconcerned, whereas participants who were alone reacted appropriately.

The original study, and many others like it since, is unhappily not limited to the academic realm. For instance, in one fire, ten people died at a Woolworths department store in Manchester, UK, all of whom died in the restaurant area. The subsequent fire investigation determined that the unusual and disproportionate number of deaths in the restaurant resulted from patrons lingering en masse to pay their bills. If people feel pressure to ignore a fire under the gaze of group dynamics, how much more challenging is it to address something much less immediately life-threatening than a fire?

The dangerous and mesmerizing power of conformity: A hotel conference suite is set up for an ostensible focus group on internet shopping; instead, it is an experiment. Far left – the smoke under the door, simulating a fire in the next room, accompanied by a smoke alarm. Second from left – the “focus group participants” alone in the room at the time of the smoke and alarm all evacuated immediately. Third from left – one “focus group participant” and seven actors; the actors, some of whom are pictured in this photo, all have instructions to ignore the smoke and alarm. Thirty-six seconds after the smoke/alarm, some people in the room are actively coughing. The actor on the left in the photo is casually chewing gum as smoke wafts by his face. Far right – the “focus group participant” looking around at the actors; upon seeing that the others in the group are not reacting, neither did this participant. This participant was in the room for twenty minutes until one of the staff running the experiment discontinued the run. Of all the participants in this study, only one in the group settings remarked on the smoke, staying in the room with the smoke and alarm for over twelve minutes after being assured by the actors that someone responsible “told us to wait right here” and “will be back soon” to let the group know what to do.

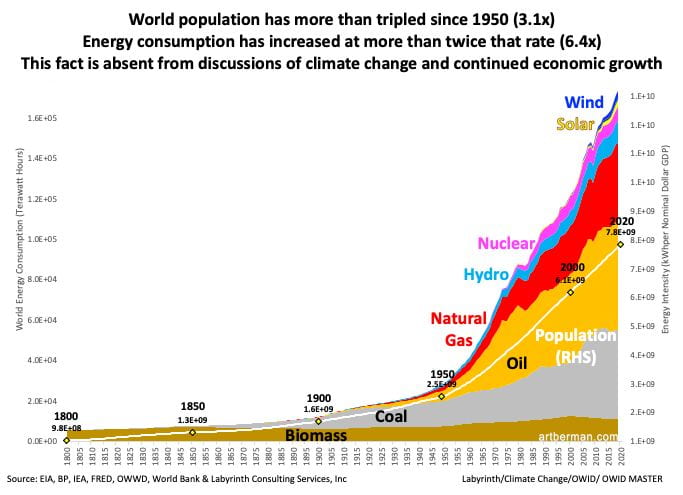

Much in discussion by Nate Hagens, his colleague and energy analyst Art Berman, many other technical experts appearing on Hagens’s podcasts and in his videos, and many scientists working on environmental and global biophysical issues, are the environmental problems that we will increasingly not be able to overcome. Hagens, Berman, their associates, and others have pointed out the following trends (for further reading, see links below):

- Records dating back to the 1800s show that new energy sources have come into use, but no energy source has ever been replaced. New energy is additive;

- Despite two decades of intense investment in renewables, renewable energy currently accounts for only a very small amount of total global energy use, and fossil fuels so far are not being replaced by renewables;

- At present and for the long foreseeable future, all renewable energy production requires materials that use substantial amounts of fossil fuel for mining, transport, processing, manufacture, and distribution;

- Steel, cement, plastic, and ammonia-based fertilizer production (what Art Berman refers to as the four pillars of civilization) all depend on fossil fuels at this time, and there is no logistically feasible mechanism on the board to change this over the time scale that it needs to be changed;

- Life as we know it on planet Earth depends on biodiversity, yet human activities underpin what is being referred to as the sixth great extinction (in the four billion years of Earth’s history).

The Inconvenient Truth – Green Edition, Art Berman, X.

One would think that the points above, and associated data, would be at the forefront of our awareness. Not so. When climate and environment are on the table, we now experience the new cultural hegemony of what is being called toxic optimism, i.e., whereby people are exhorted not to be “doomers” and thereby suppress or dismiss concepts that invoke unpleasant emotions. Author Deirdre Kent has summarized this effect and its consequences as regards climate and environmental change as follows:

- Driven by the tendency to downplay the severity of the climate and environmental change despite evidence to the contrary, leading to a delay in taking action and deference to putative technological “solutions.”

- Fostering complacency through the appealing feature of not requiring personal sacrifices or lifestyle changes, thereby guaranteeing that a collective effort to combat environmental damage fails to occur while the window of opportunity to curb the worst environmental effects continues to narrow.

- The compulsory feature of toxic optimism silences dissenting voices, raising the Power Distance Index of the dialog and supporting dangerous conformity. Individuals expressing concerns about the gravity of the climate and environmental change or proactive levels of change in lifestyles face backlash from those who adhere to the carefully scripted narrative of perpetual positivity.

- Such consistency in toxic optimism translates to the realm of policymaking, supporting decision-makers to also underestimate and under prepare for change.

Toxic optimism means well but achieves a Power Distance position that asphyxiates important-but-difficult conversations and obstructs effective collaboration. In an emergent, compulsorily optimistic world, perhaps the most radical thing said on the topics above is by Art Berman, that we need to be “Getting honest about the human predicament.”

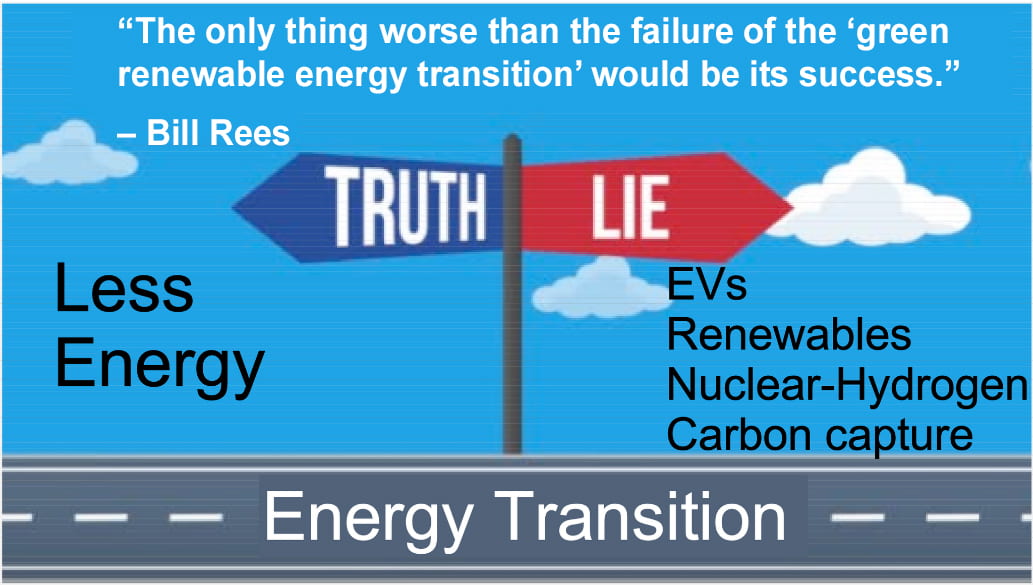

Graphic courtesy of Art Berman, X. Art spoke at the recent Meadows Center Climate Conference. His solution was clear – consume fewer materials, less energy. This is in contrast with what some have called “Toxic Optimism,” that technology, ingenuity, etc., will save the day (Note – Bill Rees is the originator of the ecological footprint concept and co-developer of the method.)

Literature on the Power Distance Index

- Walumbwa FO, Lawler JJ, 2003. Building effective organizations: transformational leadership, collectivist orientation, work-related attitudes and withdrawal behaviours in three emerging economies. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 14, 1083–1101. doi:10.1080/0958519032000114219

- Yuan F, Zhou J, 2015. Effects of cultural power distance on group creativity and individual group member creativity: Power Distance and Creativity in Groups. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 36, 990–1007. doi: 10.1002/job.2022

- Liu, S-M, Liao J-Q, 2013. Transformational leadership and speaking pp: Power Distance and Structural Distance as moderators, Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 41, 1747–1756, doi:10.2224/sbp.2013.41.10.1747

Resources on Extinctions

- Creatures United – Frankly #9 (Nate Hagens, YouTube)

- What biodiversity and nature loss mean for our economy (The European Central Bank Podcast, YouTube)

- Nick Haddad: “Insects – A Silent Extinction” | The Great Simplification #90

(Nate Hagens, YouTube)

Resources on Energy

- The SHOCKING Truth About Our Energy Crisis w/ Nate Hagens (Aubrey Marcus, YouTube)

- Substituting Renewable Energy for Fossil Fuels is a Doomsday Stratagem (Art Berman presentation to the Energy Institute – University of Texas at Austin, YouTube)

- The State of The Species 2020 (

Nate Hagens, YouTube) - Art Berman “Oil: It was the best of fuels, it was the worst of fuels” | The Great Simplification #03 (Nate Hagens, YouTube)