I arrived late to the party. It’s the story of my life. How is it that I discovered so late that there was a party? The party could not be kept a secret forever, however, from even my keenly penetrating perspicuity. So arrive I did. The party is based around the increasing use, often by non-scientists, of the phrase “follow the science.” No sooner was I aware of this (at the party) than I was also aware that, well, “you keep using that phrase; I don’t think it means what you think it means.”

By no means take my word for it. The Washington Post and the New York Times were not late to the party, and both have since published articles discussing how this phrase, rather than really having anything to do with science, has come to be used by many as an agenda-loaded rallying cry. Not that it is hard to understand why someone would want to use the phrase, for instance, to modestly suggest that we might look to facts and scientific evidence to inform our daily decisions on matters technical and/or policy decisions made for us at a local, regional, or even national level.

Everything that I am now reading and hearing about following the science leads me inevitably to the juice, lemon juice specifically, and not just lemon juice, but the specific lemon juice that Justin Kruger and David Dunning mentioned in their consideration of what they referred to as “the unfortunate affairs of Mr. Wheeler.” Mr. Wheeler had robbed a couple of banks in broad daylight with no attempt to conceal his face from surveillance cameras because he thought that his having rubbed lemon juice on his face prior to the robberies would protect him from the camera’s gaze.

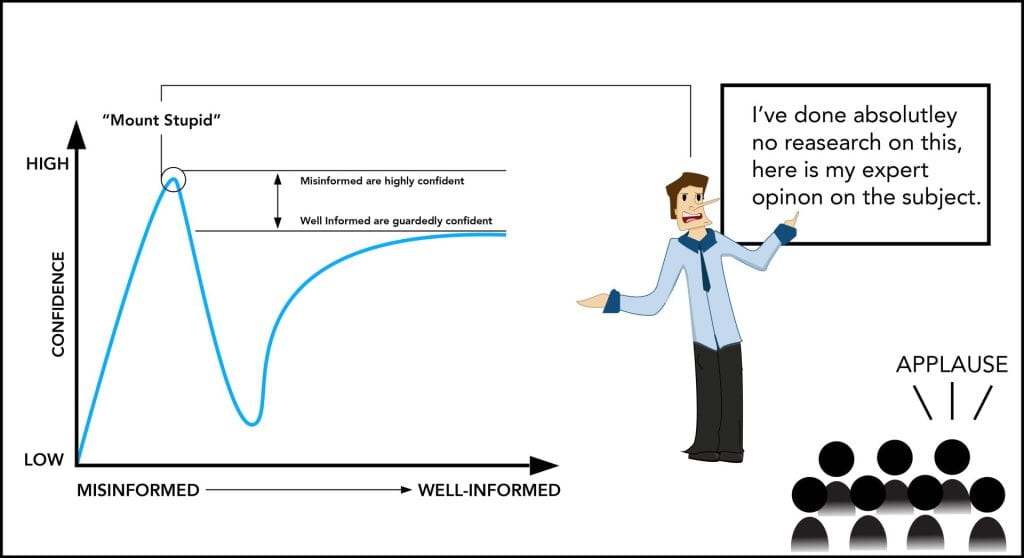

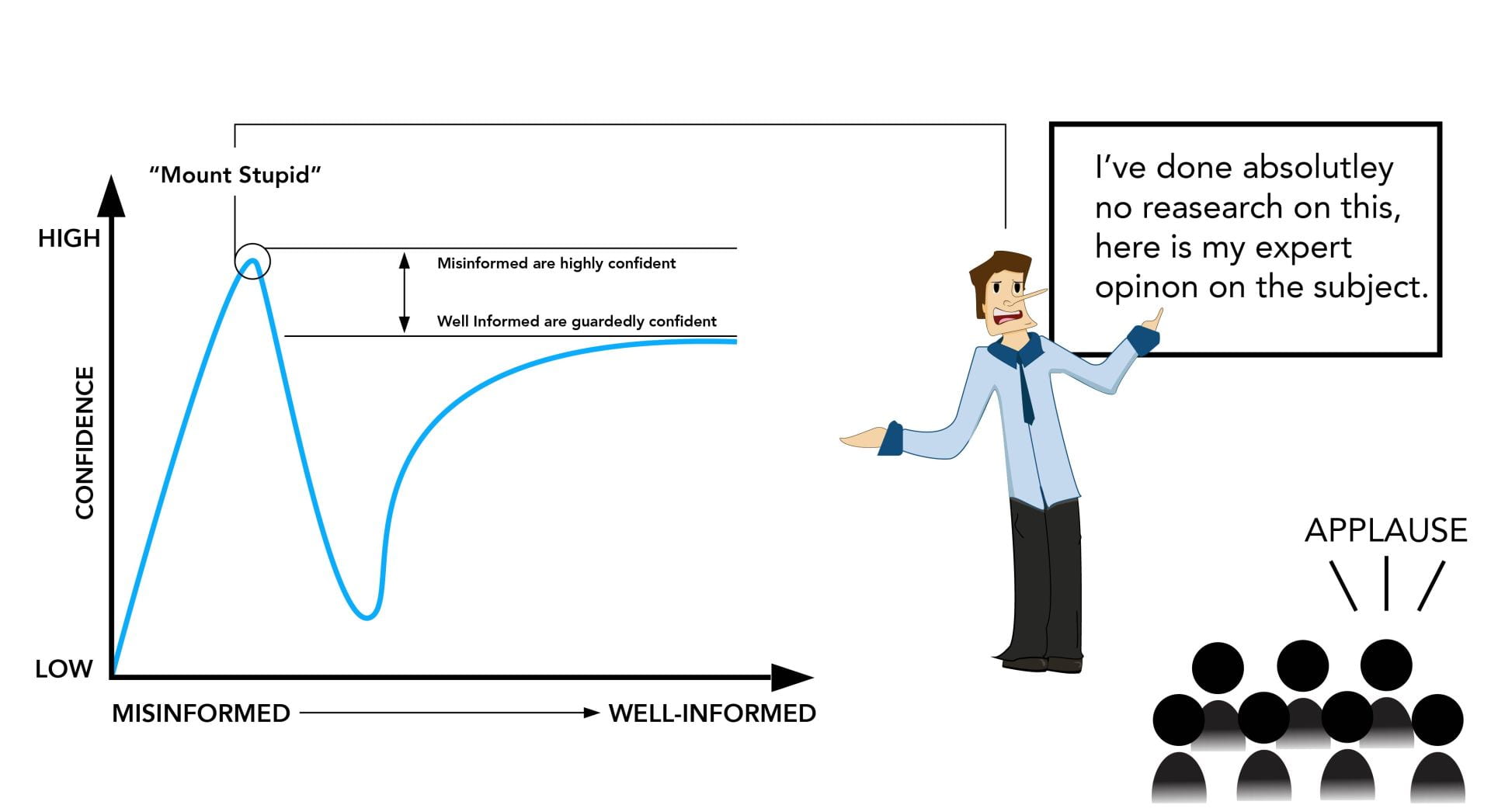

Mr. Wheeler, apparently, is not alone in misjudging his own expertise in matters that count. In a series of groundbreaking papers, Dunning and collaborators described their research demonstrating that for a variety of tasks, persons with low skills and/or ability are more likely to overestimate, sometimes greatly overestimate, their own ability. In contrast, persons with high skills and abilities are less likely to be overconfident and more likely to accurately assess the limits of their own knowledge. Such a phenomenon is now referred to as the Dunning-Kruger effect, though the concept has been around for quite some time, dating back to Socrates and including famous comments from Shakespeare (“the fool doth think he is wise”) and Darwin (“ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge”).

In the last two decades, Dunning has observed the effect in a wide array of manifestations. In one study, he found that 90% of respondents considering themselves “well-versed” claimed knowledge of made-up, nonexistent scientific terms such as “plates of parallax” and “cholarine.” Respondents considering themselves politically savvy asserted their knowledge of Michael Merrington (a made-up character), and those who had declared bankruptcy had a high estimation of their financial savvy, despite also having low scores on fiscal literacy tests. Dunning’s research makes fantastic humorous reading; however, it has a serious and alarming side to it. Dunning comments

“What’s curious is that, in many cases, incompetence does not leave people disoriented, perplexed, or cautious. Instead, the incompetent are often blessed with an inappropriate confidence, buoyed by something that feels to them like knowledge.”

It would be nice to be immune to Dunning-Kruger effect, but, according to Dunning, none of us should rush to judge the idiocy of others—unrecognized ignorance is a pitfall for all of us, even the vigilant. Dunning describes it as being misinformed and, moreover, being so because our species has an inherent propensity for purpose-driven reasoning that often misfires. The answer to avoiding being one of the misinformed? Knowledge (!) and upskilling, of course, but not necessarily “education,” which Dunning’s research indicates sometimes fails to disabuse students of incorrect premises while simultaneously instilling misguided confidence.

What, you may be asking yourself, does all this follow-the-science party, juice, Mr. Wheeler, or even Dunning-Kruger effect have to do with climate science at the Meadows Center? Climate affects water and is a highly contentious topic these days. The Meadows Center scientists are aware of the dangers of misinformation, including that even experts may fall into its trap. Although they are not as charming and engaging as I am (leading to my needing to bandit this blog), they are careful to scrutinize their own research. In addition to the Meadows Center mission to provide evidence-based science, Meadows Center scientists are also concerned with the analysis of uncertainty, i.e., the fact-based boundaries of their knowledge. They are not striving to have anyone “follow” their science; rather, they provide scientifically rigorous, evidence-based information for use by a multitude of stakeholders who might wish to take a shortcut around the misinformation highway.

“Following” the Habanero, however, is another matter. The Habanero is a way to stimulate discussion, which possibly explains why the Meadows Center even graciously indulges me, as long as I roll up with (some) sensible and facts-based commentary. “Follow the Habanero”—a nice maxim! What do you think, would it be too extreme to claim it as a life philosophy? Let us know in the comments →

Further Reading:

- ‘Follow the science’: As the third year of the pandemic begins, a simple slogan becomes a political weapon (The Washington Post)

- Follow the science? If only it were so easy (The New York Times)

- We Are All Confident Idiots (Pacific Standard)

This was so much fun to read!