Written by contributors from a variety of backgrounds and expertise, Global Perspectives is a new series from the Habanero that reveals how people across the world are coping with and adapting to an increasingly extreme climate. In this post, we invited scientist Boris Tefsen from the Netherlands to tell us about his climate-related experiences.

On 24 February 2022, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic largely disappeared from the news.

On that day, Vladimir Putin ordered Russian troops into Ukraine, and many governments of countries in the European Union and beyond immediately looked at their gas storages and at their dependency on Russian gas.

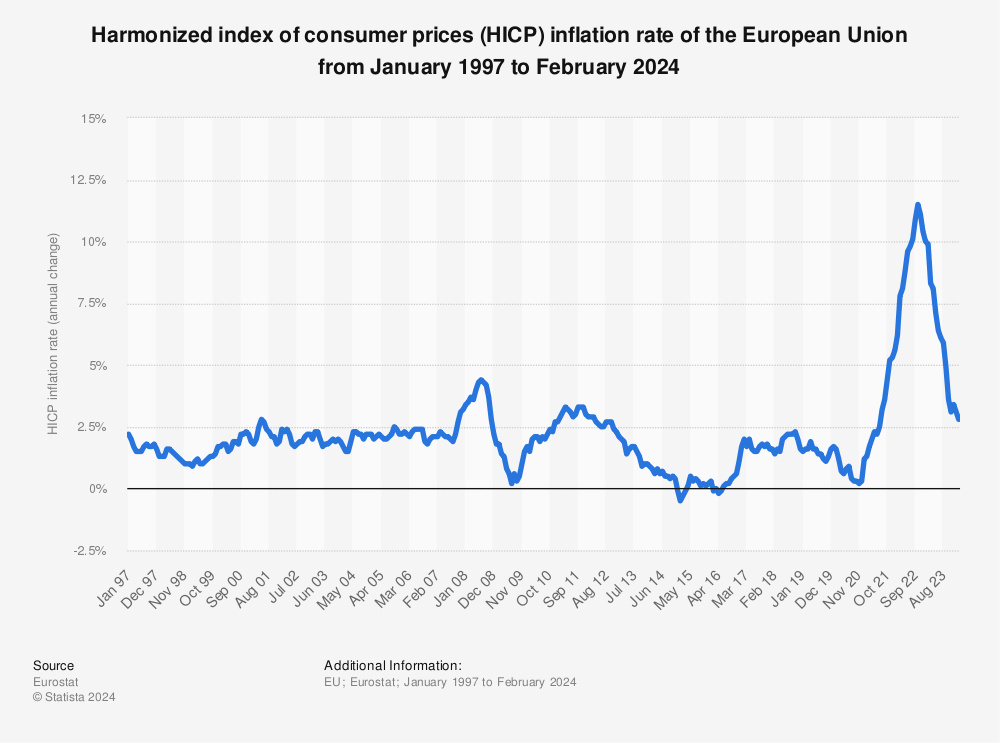

And at the rising inflation.

Find more statistics at Statista

Then they took a deep breath and decided to put sanctions on Russia anyway, resulting in the following gas prices.

Households in the Netherlands were facing huge increases in their energy bills, which could amount to several hundreds of Euros per month on top of their usual costs (for instance, the average bill in a winter month for a family of four living in a free-standing house is calculated to be 1200 EUR, equivalent to $1,300 US). For people without savings, this would mean they would have to find ways to cut their monthly costs elsewhere, or start lowering their gas consumption.

So that is what happened almost immediately and is still ongoing, despite interventions like a price cap by the Dutch government to soften the financial blow.

What can we learn from this? First of all that together, around 18 million people are able to lower their gas consumption by around 25% when there is a monetary incentive.

We know that burning natural gas produces carbon dioxide, one of the major greenhouse gases that has been rising steadily and contributes to warming up the planet. There are efforts to replace fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas with other sources that do not produce carbon dioxide, like solar, wind and nuclear, but they also come with their own (environmental) issues. The cleanest way to get less carbon dioxide into our atmosphere is simply to use less energy. Just like what has been happening in the Netherlands and many other countries in Europe for the last year.

So how is this 25% saving achieved? For example by not heating any rooms that are not used a lot, closing doors and windows of warm rooms, putting the thermostat 1, 2 or 3 degrees lower than the Dutch government’s currently recommended temperature of 19°C (66 °F) during the times one is inside and putting it much lower when one is sleeping or not in the house at all and lowering the thermostat one hour instead of 1 minute before one goes to bed. Shower less often (not healthy anyway), shower shorter and at a lower temperature. Boil the amount of water you need for a cup of tea and not an excess amount of water.

What does this all actually mean for daily life?

You might need to dress warmer inside, move around a little more and be more conscious of time when taking a shower.

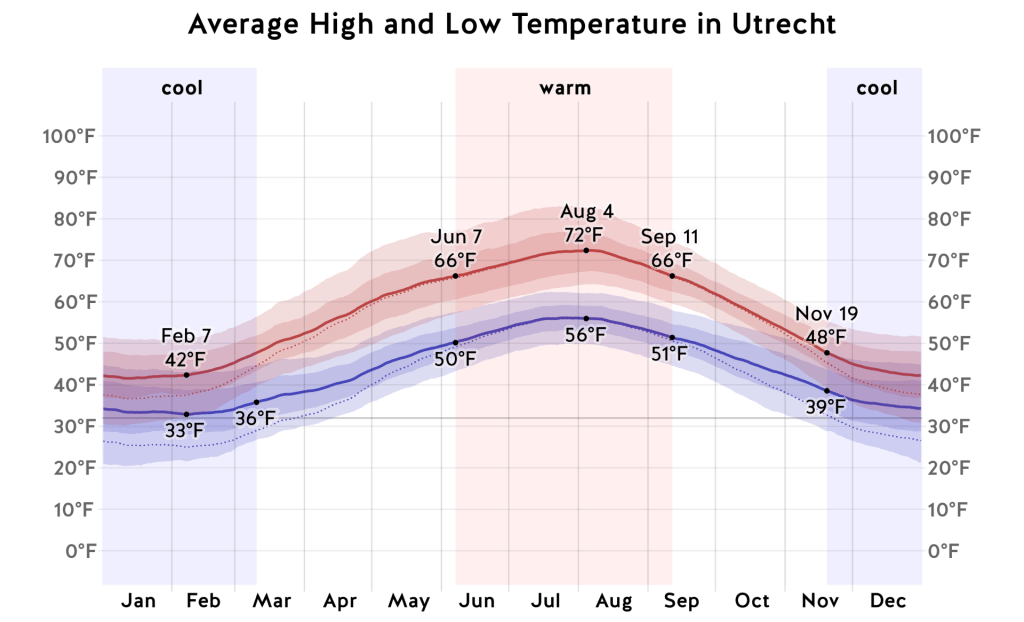

Is that bad? Does it make life less worthy? I guess the answer to that will depend on the individual and where they live (you can take a look at the average monthly temperature for Utrecht, Netherlands, a city in the middle of the Netherlands, and compare it with your area).

The daily average high (red line) and low (blue line) temperature, with 25th to 75th and 10th to 90th percentile bands. The thin dotted lines are the corresponding average perceived temperatures. Source: © WeatherSpark.com

As of writing, gas prices have gone done to below levels at 24 February of last year. It will take a while for those prices to be incorporated in the ones paid by households and perhaps developments in the world will change again soon. But it will be interesting to see if those new energy-saving habits will stick for the long run. It might be a bit cooler at home, but it will also slow down the heating up of our planet.

Boris Tefsen is a lecturer at the Faculty of Science at Utrecht University, the Netherlands. He has always been fascinated by nature and, in particular, the diversity of molecular mechanisms in cells. His recent interests are environmental pollution by heavy metals and antibiotics and the many ways these affect microorganisms like soil bacteria and cyanobacteria living in freshwater.