I recently asked the Climate Bandit, “What’s the best thing someone can do to reduce their carbon footprint?” He/she/they (the Bandit is a shadowy, quixotic, and somewhat asexual individual) thought for a few beats, and then responded, “Seppuku.”

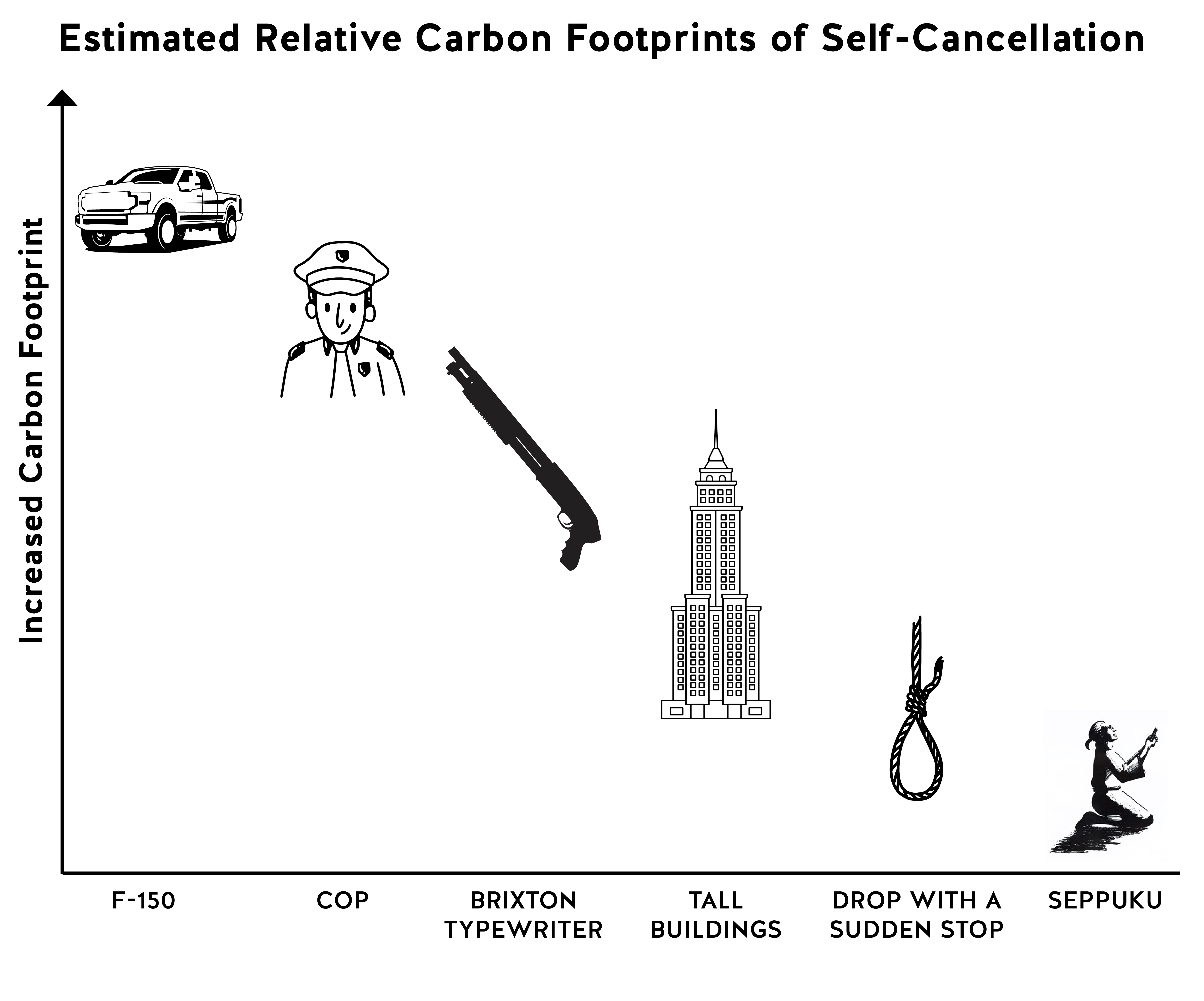

That seems extreme. In case you aren’t familiar, seppuku is the Japanese version of self-disembowelment (I’m looking at you, Yukio Mishima). It’s also perhaps a bit inconvenient (my wife: “What are you doing? If you drop your liver on the rug, I’M GOING TO KILL YOU!!!”). Seppuku certainly has a smaller carbon footprint than carbon monoxide poisoning (Figure 1), so I’ll give the Bandit that. However, death by Ford F150 has a certain poetry to it.

Figure 2: Average annual precipitation (from the 2012 State Water Plan).

I’ve been reading a poo-ton of books on climate change, many written for the public. A couple composed by academics, Saving Us: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope and Healing in a Divided World by Katharine Hayhoe and Under the Sky We Make: How to Be Human in a Warming World by Kimberly Nicholas, have similar answers to my “What’s the best thing?” question: “Do what you can.” Both point to changes at the highest levels of policymaking as the most important thing, changes that will lead to substantial declines in carbon emissions and a meaningful transition from our current carbon culture.

Initially, “Do what you can.” seemed weak to me. Do what you can? Really? Sounds a little lame when the world is (literally) burning. But after additional pondering, more reading, and recently being carbon shamed, I realized that Hayhoe and Nicholas are right. At a personal level, do what you can. Big changes require, well: big changes. And those changes occur at the state, national, and international levels. Carbon shaming does not help and probably actually hurts. People generally rebel against other people telling them how to live. Not to mention that all of us, including the tellers, are guilty of carbon sin (He that is without sin among you, let him cast the first stone…). The sword awaits.

In my own life, I drive an electric car powered 100% by renewables, our home is powered 100% by renewables, I offset plane rides, and I minimize eating beef (although more for health reasons than anything), among other things. We still use natural gas for heating and cooking, but we offset that use. And from time-to-time, I eat bugs, but not religiously (no praying mantis for me). There’s still a lot of embedded carbon that I’m not considering, but I’m doing what I can.

Do I expect others to live the way I do? I don’t. Not everyone can afford an electric car (although prices are coming down) or make one work with their life (it would be a challenge to haul hogs in Gruver). Not everyone has a roof amenable to solar, the extra cash to install it, or a roof they own. Most Americans do not have access to good public transport; if they do, it’s poorly run or poorly merged with modern life. And how the holy hell do you resist Aaron Franklin’s brisket? But do what you can. Policy, culture, and the infrastructure of modern life don’t change overnight.

I just finished a cli-fi novel by T.C. Boyles titled Blue Skies. Unfortunately, I’m not sure I fully understand the novel’s undercurrent. But I think the book’s point is that regardless of an individual’s actions in response to climate change (oblivious, concerned, educated, worried, career-dedicated, despondent), we’re all riding the same elite-controlled societal tidal wave, regardless of what we are doing and how concerned we are or aren’t. Some people, the people at the highest levels of decision making, do have some semblance of control, but even they are riding the wave.

Doing what you can is not an invitation to do nothing. It’s to do what you can. If you can, then maybe you should. Could I do more? Certainly. A seppuku sword can be had for $100 on eBay. But that’s also a bit inconvenient for my lifestyle. In my home, we do what we can, strive to do better, and keep an eye on the broader societal aspects and the small but collective role our votes and voices play. Live softly, but support a big policy change.

Note on electric cars: There’s quite a bit of propaganda against electric cars out there. Yes, they tend to have twice as much embedded carbon than gasoline-powered vehicles, and the overall carbon benefits depend on how your power company generates electricity. But an electric car 100% powered by renewables reaches carbon parity with a gasoline-fueled one at about 15,000 miles. Every mile driven after that in an electric is pure carbon savings over a gasser.

Note on carbon offsets: There’s a lot of legitimate chatter about how effective carbon offsets are. For example, we rented a gasoline-fueled car for vacation for 1.5 weeks, and the carbon offset cost from the rental company was a rip-roaring $1.25. I’m not an expert in carbon offsets, but I know that can’t be right; in fact, it’s ridiculously wrong. Like many things, the effectiveness of a carbon offset depends on many factors. Regardless, I’m happy there’s an attempt, an attempt that will hopefully get better with time.

Fascinating commentary on EV’s. However, no explanation on the earth impact on EV battery manufacture nor the impact of composite turbine blades for wind “farms”. I’m interested to hear discussions on this. Still, glad to see movement to regain good stewardship of our planet.

Thanks 4 Mishima reference. Do what you can during this hottest week on earth.

Thanks 4 Mishima reference. Do what you can during this hottest week on earth.