“Every time I pray for rain, I’m afraid the Lord will give me what I deserve, not what I want.”

–Brooks Gunter, farmer on the Texas Panhandle*

Although Texas is better prepared for drought now than in the late 1900s, the state is less ready for a repeat of the drought of record—or worse—than it was back then. If that sounds counterintuitive, it’s because all droughts are not created equal.

Drought anyone? Hang onto yer britches. Source: USA Today

Before the mid-nineties, two decades of cooler and wetter weather lulled Texas into complacency, turning the Dust Bowl and the Drought of the 1950s into hazy, distant memories. The drought of 1996, which fundamentally changed water planning through 1997’s Senate Bill 1, was almost comically mild compared to what Texas has been through since. But at the time, with only weeks of water left for several small communities, the drought was no laughing matter. In response, Lieutenant Governor Bob Bullock led the legislature to change water planning, and the water culture, in Texas by steeping stakeholders into every aspect of water, creating a toothy bottom-up approach rather than the toothless top-down decreeing.

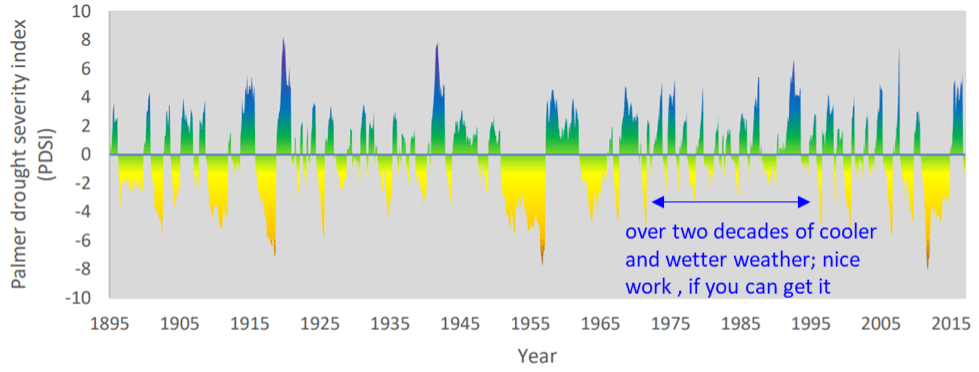

The Palmer drought severity index (PDSI) is a measure of drought that is calculated using readily available temperature and precipitation data. This index has values from negative 10 (-10, dry, light green to yellow to dark orange) to plus 10 (10, wet, dark green to blue to purple). The diagram above shows how this index has varied from 1895 to 2015. The blue arrow shows the over two decades of weather from the 1970s to the 1990s that lulled Texans into forgetting our drought problems. Source: Texas Water Development Board

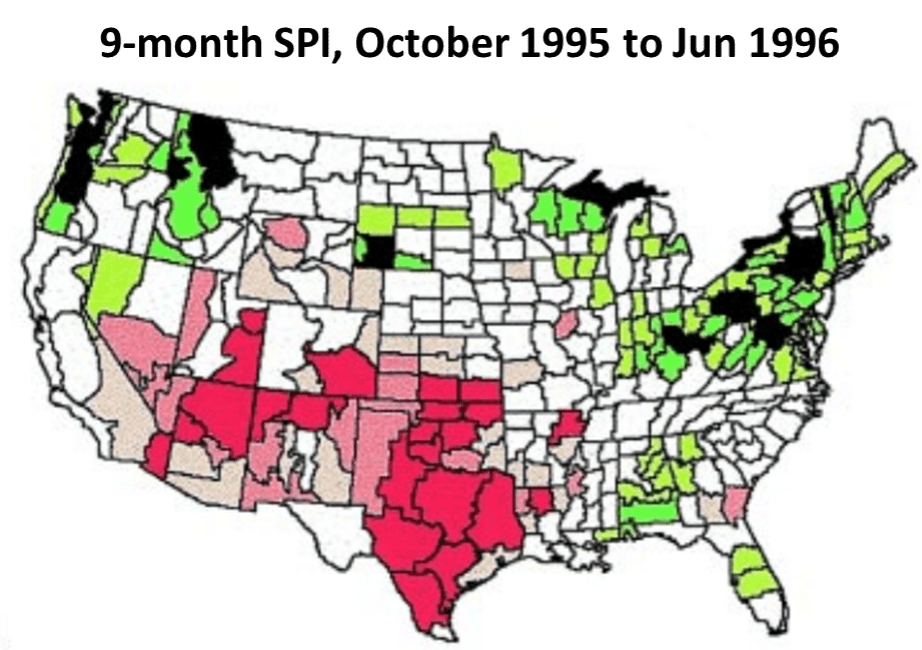

Droughts are difficult to detect and monitor. While the Palmer Drought Severity Index has been extensively used, it did not predict the 1996 drought in Texas until after the drought was well underway. Recently, the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) was developed to improve drought detection and monitoring capabilities. During the 1996 drought, the SPI detected the onset of the drought at least one month in advance of the PDSI, a timeliness invaluable for improving response actions. The figure here shows the cumulative effect of the drought by the end of June 1996; red is an SPI of -4, where an SPI of -2 is already “extremely dry.” Source: University of Nebraska – Lincoln

This bottom-up planning, financing, and drought response system has worked brilliantly. Texas has suffered far worse droughts since 1996, including the worst one-year state-wide drought of record in 2011 and the second-worst overall drought of record between 2011 and 2015. Setting aside agricultural and environmental impacts, Texas faired reasonably well with no communities running out of water (if you want to fight about Spicewood Beach, I’ll meet you out back). But this brilliant system has not worked perfectly.

According to National Public Radio, the town of Spicewood Beach, outside of Austin, was the first town in Texas to run out of water, in January 2012, as a result of the drought that started in 2011 (above left, photo of water delivery in Spicewood Beach, 2012). Above right – if you want to fight with the author about the accuracy of the report. Note the luxuriant green grass in the background of the photo to the left. Sources: left photo – State Impact, right photo – imgflip

With each state water plan published since the passage of Senate Bill 1, Texas has fallen farther and farther behind in being ready for The Big One. For example, water needs in the first planning decade for a drought of record have doubled from 2.4 million acre-feet in the 2002 State Water Plan to 4.7 million acre-feet in the 2022 plan. The state-wide drought of 2011 to 2015 was pretty dang bad, but it would have had to burn for two more years to match the drought of the 1950s. With Wichita Falls’ reservoirs evaporating before their eyes and many West Texas towns losing or at risk of losing their water supplies, we narrowly avoided economic and humanitarian disasters across the state.

The drought of 2011 in Texas; disaster narrowly averted. Source: Statesman Photo & Multimedia Blog

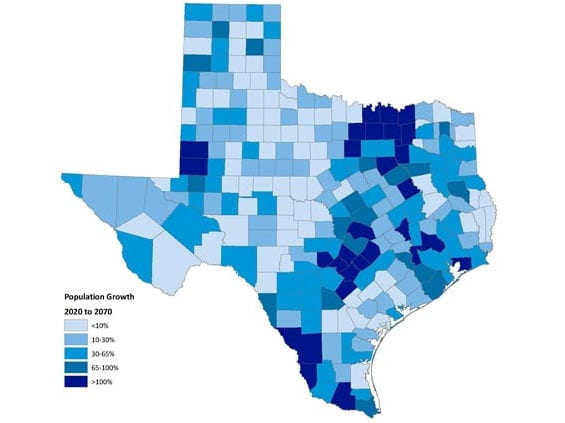

Part of the problem is that drought resiliency is a moving target. As Circle of Blue’s article on population growth and water supplies notes, the growing number of Texans in the bedroom communities circling our urban cores rocks one side of the water-planning equation while drought hard places the other side. And as Central Texas and other parts of the state discovered in the 2010s, a drought of record can be easily out-droughted.

Expected population growth of Texas from 2020 to 2070, according to the Texas Water Development Board. All these people are going to need water.

Compounding these difficulties is that, in a warming climate, surface runoff and groundwater recharge generally decline while drought becomes more and more likely. A recent paper published in Earth’s Future notes that in the second half of this century, under a high-emissions scenario, Texas’ climate could rival the driest periods seen over the past 1,000 years. Even setting aside climate change, tree ring data shows that Texas has suffered far worse droughts than the ones we’ve had over the past 150 years of the record.

As Benjamin Franklin didn’t exactly say: “Nothing is certain in Texas except death, low taxes, and drought.” Accordingly, if there’s one thing Texans know, it’s the importance of water. And Texas has done some fantastic things for drought resiliency, including regional water planning, stakeholder processes, drought management plans, water conservation plans, and financing the state water plan. But we’re still vulnerable to The Big One, and The Big One—or worse—becomes more likely every day. To get what we want—drought resiliency—we’ll need to do more, such as implementing the plan we have and taking a closer look at (and planning for) what’s coming. What do you think? At the very least, is that what we deserve? Let us know in the comments →

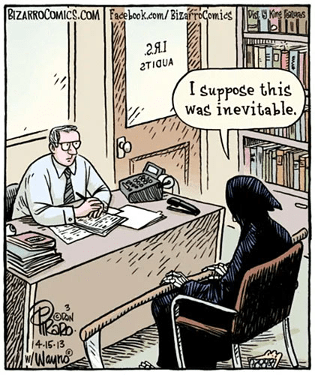

In this cartoon, it may appear that the Grim Reaper, death, is being subject to a tax audit. In reality, however, Mr. Reaper and the Internal Revenue Service tax auditor are discussing the inevitability of “this” drought in Texas.

*The quote from Brooks Gunter is from a Washington Post article written by Sue Anne Pressley and published on April 1, 1996.

Outmigration–we’re gonna have to move to the water

Outmigration is the only long term solution. Start in the desert southwest and proceed east and north til the water doth suffice. Pipes and dams won’t work without rain. Rust belt or bust.